Unveiling TF Footprinting in Neurodegeneration

- 5 minsIntroduction

Understanding transcription factor (TF) binding is essential for unraveling the complex regulatory networks underlying gene expression. Tools like scATAC-seq offer unprecedented opportunities to study chromatin accessibility at the single-cell level, shedding light on gene regulation and its dysregulation in disease. However, existing methods for analyzing TF networks often fall short of distinguishing functional TF binding from non-functional motifs. In this blog, we explore a novel approach leveraging TF footprinting to overcome these limitations, offering new insights into neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) and Pick’s Disease (PiD).

Challenges in Current Methods

Widely used methods such as SCENIC (Aibar et al., 2017) and SCENIC+ (Bravo González-Blas et al., 2023) rely on conventional motif enrichment analyses to construct gene regulatory networks (GRNs). While SCENIC uses promoter regions and co-expression patterns from scRNA-seq data, SCENIC+ extends this by integrating scATAC-seq and scRNA-seq data to link enhancers to target genes.

However, these methods have notable limitations:

- They infer TF activity indirectly through overrepresented motifs, which can lead to false positives.

- They struggle to distinguish functional enhancer-TF interactions from non-functional motifs.

For instance, a multi-omic study in AD (Mathys et al., 2024) demonstrated the utility of SCENIC in constructing cell-type-level TF regulators in AD snRNA-seq data. SCENIC+, on the other hand, builds on this by using pycistarget, a wrapper for HOMER, for enhancer motif enrichment. Unfortunately, these approaches often miss the mark in identifying true TF binding events.

Limitations of Using Open Chromatin as a Regulatory Marker

A common assumption in chromatin accessibility studies is that open chromatin regions correlate with active regulatory elements. However, recent findings challenge this notion.

Studies like Xiong et al., 2023 revealed that increased chromatin accessibility in neurodegenerative diseases often reflects chromatin relaxation rather than functional regulation. Similarly, Frost et al., 2014 observed chromatin relaxation and heterochromatin loss in tauopathies such as PiD and AD. These ‘relaxed’ chromatin regions may not indicate meaningful regulatory activity, as they often lack functional TF binding.

Further complicating the picture, Baek et al., 2017 reported that 80% of TF binding motifs do not show measurable footprints, suggesting that open chromatin alone is an unreliable indicator of active regulation. Methods like SCENIC and SCENIC+ may still infer TF activity in these regions, potentially resulting in false positives.

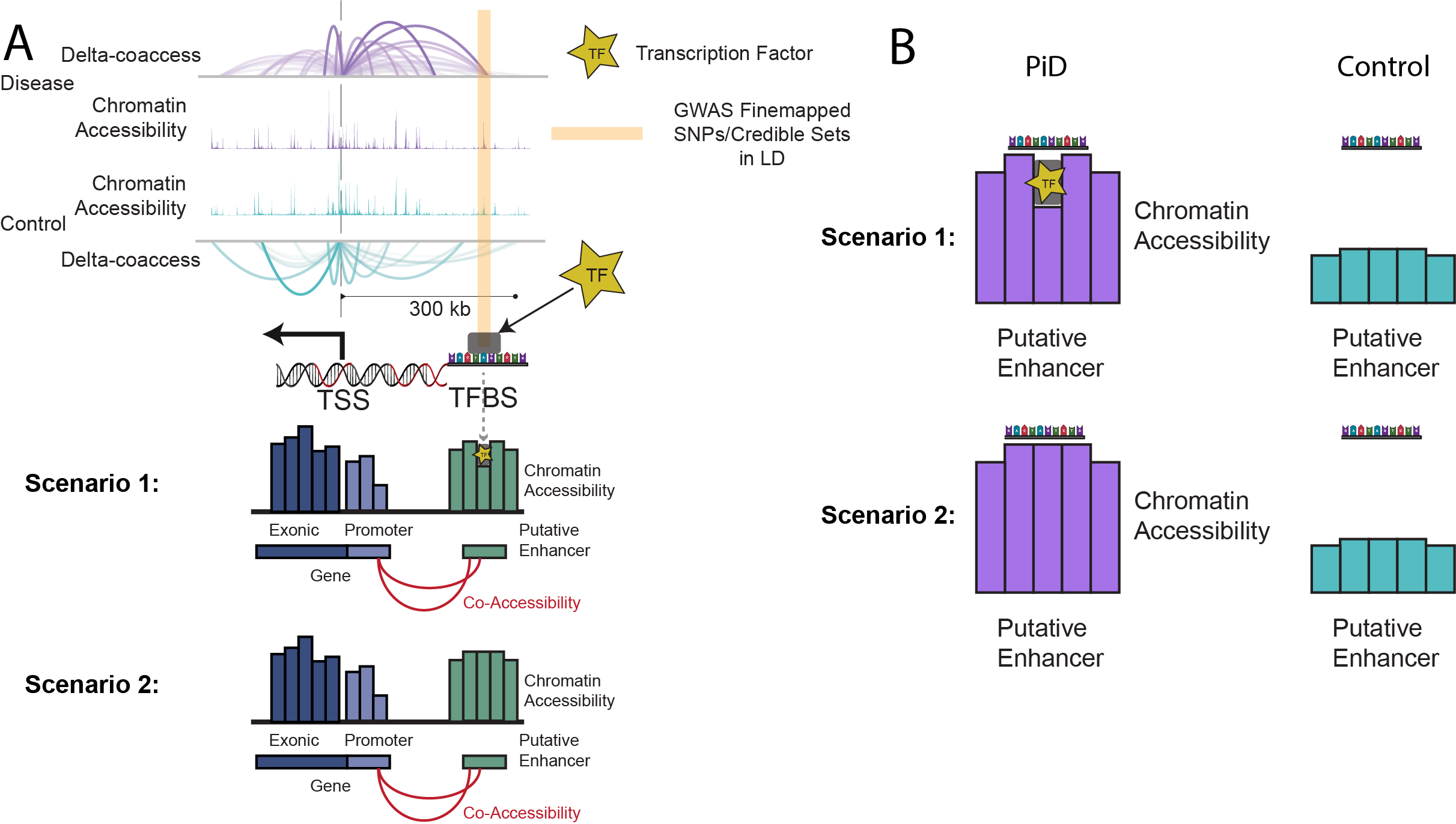

This phenomenon is illustrated in Fig. 1 below, where we depict two scenarios: (1) open chromatin regions with TF binding (‘functional regulation’) and (2) open chromatin regions without TF binding (‘chromatin relaxation’).

Open chromatin = active regulation → Not always true.

These findings show that many accessible regions:

- Are not bound by TFs

- Reflect global chromatin decondensation

- Are easily misinterpreted as regulatory by motif-based methods

Open Chromatin Scenarios

Fig. 1 shows two key scenarios of transcription factor binding in open chromatin regions. Scenario 1 highlights regions where open chromatin coincides with functional TF binding, while Scenario 2 depicts regions with open chromatin but without active TF binding, indicating chromatin relaxation rather than regulation.

A Functional TF Footprinting Approach

To address these challenges, we reimplement a bulk ATAC method on single cell data that incorporates TF footprinting and motif-flanking accessibility using the TOBIAS (Bentsen et al., 2020) package. This approach offers a more accurate and confident way to identify active TF binding events.

1. TOBIAS calculates TF occupancy across all accessible chromatin regions, allowing us to:

- Distinguish TF-occupied enhancers from non-functional motifs.

- Assess footprinting at binding sites and motif-flanking accessibility.

- Compare TF occupancy between disease and control conditions.

2. Key Advantages of the TF Footprinting Approach on Disease Related Regulatory Network:

- Direct Measurement of TF Occupancy: Unlike SCENIC and SCENIC+, which rely on motif enrichment, our method directly measures TF binding, reducing false positives.

- Higher-Resolution Insights: By distinguishing functional enhancer-TF interactions from non-functional motifs, we provide a more accurate view of regulatory networks.

- Enhanced Integration: Combining snATAC-seq and snRNA-seq data allows for comprehensive analyses of TF-mediated regulation in specific cell types.

Implications for Neurodegenerative Disease Research

This method holds significant promise for advancing our understanding of transcriptional regulation in neurodegenerative diseases like AD and PiD. By uncovering true TF binding events and regulatory interactions, we can identify novel therapeutic targets and gain new insights into disease mechanisms.

For example, this approach can help clarify the role of chromatin accessibility changes in neurodegeneration, distinguishing functional regulation from non-functional chromatin relaxation. Additionally, it provides a valuable resource for exploring TF activity and its implications in disease contexts.

Key Notes:

- True disease-associated TF binding events

- Functional enhancer dysregulation

- Misleading “relaxed” chromatin not involved in regulation

- Candidate TFs and enhancers for therapeutic exploration

Conclusion

This functional TF footprinting approach represents a major step forward in regulatory network analysis, addressing the limitations of conventional methods like SCENIC and SCENIC+. By leveraging tools like TOBIAS to measure TF occupancy directly, we can distinguish functional regulatory events from non-functional motifs, providing deeper insights into gene regulation in neurodegenerative diseases. As we continue to refine these methods, they will undoubtedly play a critical role in shaping the future of genomic research and therapeutic discovery.

References

-

Aibar et al., SCENIC: single-cell regulatory network inference and clustering. Nat Methods (2017).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.4463 -

Bravo González-Blas et al., SCENIC+: single-cell multiomic inference of enhancers and GRNs. Nat Methods (2023).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-023-01938-4 -

Mathys et al., Single-cell multiregion dissection of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature (2024).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07606-7 -

Xiong et al., Epigenomic dissection of Alzheimer’s disease. Cell (2023).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2023.08.040 -

Frost et al., Tau promotes neurodegeneration through global chromatin relaxation. Nat Neurosci (2014).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.3639 -

Baek et al., Bivariate genomic footprinting detects changes in transcription factor activity. Cell Reports (2017).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2017.05.003 -

Bentsen et al., ATAC-seq footprinting reveals TF binding kinetics. Nat Commun (2020).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-18035-1